The operation of shame - "Operation asphalt" was carried out by excavating war graves in Norway and moving to Tjøtta, south of Nordland, Norway.

The operation of shame - "Operation asphalt" was carried out by excavating war graves in Norway and moving to Tjøtta, south of Nordland, Norway.

When the Nazis entered Ukraine in 1941, many Ukrainian soldiers and civilians were captured. Hitler feared Allied invasion and had a notion that Norway was an area of destiny.

Nearly 50,000 Ukrainian prisoners of war ended up in German concentration camps in Norway and were good laborers for the Nazis. Under slave-like conditions, they worked at industrial, transport and defense facilities throughout the country. They built the Nordlandsbanen, airports at Kjevik, Bardufoss and Gardermoen and the railway through Nordland to Bodø. Many Norwegians became involved in the fate of the Ukrainian prisoners and the inhuman conditions they lived under in German captivity. Some tried to help and put their own lives at risk. The Ukrainian prisoners and their significance for Norway are a forgotten chapter in Norwegian war history, also from a political point of view. Several thousand of them died in Norway and were buried in the military. A significant responsibility for the graves of these Ukrainian prisoners of war lies with the Norwegian authorities.

In Norwegian foreign policy history, the war grave case is referred to as bizarre, and is pointed out as one of several specific bilateral controversies that helped to acidify and limit relations. The conditions surrounding "Operation asphalt" have also been mentioned in the media in recent times.

Historian Torgrim Titlestad characterized the excavation as both macabre and morbid. One gave more or less the bluff in popular opinion in the north.

The relocation of Ukrainian war graves was closely linked to the Cold War policy and the Norwegian authorities' fear of Soviet espionage was a major motive for its implementation. "Operation asphalt" occurred during the Korean War, when the international level of tension deteriorated dramatically. The population of northern Norway expressed fright and anger during the operation. Macabre details about the exhumation of Ukrainian victims were published in many newspapers, and people demonstrated in several places in protest against the relocation of the graves. The plans, implementation and subsequent reactions related to the operation give the impression that the Norwegian military and state authorities were in too much of a hurry and had not anticipated the great commitment among the population.

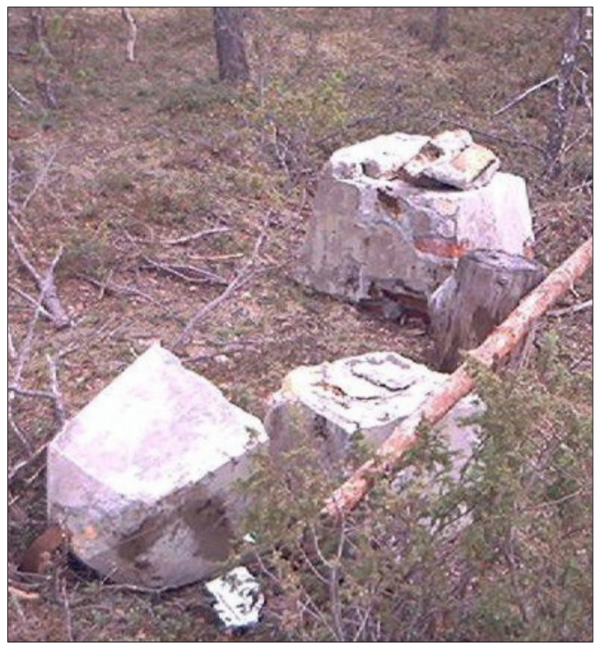

The Norwegian government then wanted to move the remains of dead Soviet prisoners of war from Finnmark, Troms and Nordland to Tjøtta war cemetery on the Helgeland coast off Sandnessjøen. The work with the move was probably given the cover name "Operation asphalt" because the excavated bodies were transported in asphalt bags. The planning of "Operation asphalt" began in 1948 with a view to establishing a common burial site at Tjøtta.

The Norwegian authorities' view was that Tjøtta would function well as a central burial ground for all the Ukrainian citizens who lost their lives in northern Norway. In total, "Operation asphalt" included approx. 200 cemeteries of which 95 in the three northernmost counties.

The Norwegian authorities' view was that Tjøtta would function well as a central burial ground for all the Ukrainian citizens who lost their lives in northern Norway. In total, "Operation asphalt" included approx. 200 cemeteries of which 95 in the three northernmost counties.

The relocation of the Ukrainian prisoners of war was completed in 1951. According to information from the War Graves Service by Eugen Syvertsen, a total of 7453 Soviet soldiers were buried in the war cemetery. In retrospect, several victims have been buried at Tjøtta. In 1952, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that 8,804 dead had been transferred to Tjøtta, of which 978 had been identified. It was clearly difficult to determine an exact figure after the move was completed, the figures given by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1952 do not match what is stated on the monument at Tjøtta. The monument lists 6725 unknown and 826 named buried.

Vladimir Nikolayevich Kalnin survived the German prison camp in Vladimir-Volynsk in Ukraine and was later sent to Kirkenes. He describes the prisoners' sad fate in Ukraine, but also helpful Norwegians:

We were sent to the Lutsk prison. The building was terrible: a terrible stench, damp and not a single dry place to stand. It was plank beds with two or three levels. Sick people were everywhere. They were dying. In this prison I met the lieutenant colonel from my squad. Since then we have been together. It was cold outside, September October, and I only had a shirt and no hat. Summer shirt and summer pants. The lieutenant colonel insisted that I find some clothes, otherwise I would die of cold and not of hunger. We started to see where we could get clothes. On a plank bed we saw a young sailor, who was dying. As soon as he was dead, we went to him to take his coat. We managed to take off his coat, but I could not put it on, it was a dead man's coat. Now I could even sit by a dead man and eating a meal, it did not bother me. I took the coat with me and wore it for several days. Eventually it got too cold and I put on my coat. Later we were sent to a concentration camp and Khelm. There were several camps there. In each camp there were 60,000 people. People died like flies, 30-40 every day. Dead bodies were taken in a truck every day. Even though the cemetery was just outside the fence, there were always more corpses to remove. The cemetery was actually a ditch. The dead bodies were thrown into the ditch and covered with a thin layer of earth. The buried bodies looked like skeletons, very thin. In Khelm we did not know each other, and we did not see each other.

This changed when he was sent to Norway:

In Norway we helped each other, we shared everything… bread ... cigarettes. We arrived to Kirkenes and Norwegians helped us a lot. Thanks to the Norwegians not many prisoners of war died, only one or two in several days. We ate everything we got. People died mostly from hunger, not from infection. The camaraderie between the prisoners and helping Norwegians kept the spirits up, tells Vladimir Nikolayevich Kalnin

For the descendants of the victims from Ukraine, it means a lot to know what happened to their relatives in Norway during the war years. They are looking for answers to where a brother, father, grandfather or uncle is buried, and want to know if the burial sites are taken care of. Separate international rules are laid down in Article 120 of the 3rd Geneva Convention of 12 August 1949 to preserve information on dead soldiers and prisoners of war. The Convention sets out the individual countries 'obligations to take care of other nations' war graves after the end of the war. The Norwegian authorities' view of the convention was nevertheless that it could not be used without further ado in peacetime, but included the warring parties in a war. This attitude has probably weakened the Norwegian authorities' understanding of their responsibility to take care of Ukrainian war graves in Norway. The Ukrainian war cemeteries in Norway are subject to permanent protection according to international conventions. The war cemeteries are subject to the Geneva Convention of 1949 and are administered by the War Graves Service unit in the Ministry of Culture. Finds of graves and remains partly arouse strong feelings in most people, and the closer such finds are to our own time, the stronger the emotions will be.

Ukrainians who are looking for and want to remember their relatives, fallen soldiers, prisoners of war and forced laborers, deserve a separate memorial in central Norway.

Comments powered by CComment