Holodomor a Genocide?

He had no money, no office, no assistant. He had no U.N. status or papers, but the [U.N.] guards always let him pass. . . . He would bluff a little sometimes about pulling political levers, but he had none. All he had was himself, his briefcase, and the conviction burning in him. We would say to him: Lemkin, what good will it do to write mass murder down as a crime; will a piece of paper stop a new Hitler or Stalin? Then he put aside cajolery and his face stiffened. “Only man has law. Law must be built.”

A. M. Rosenthal, A Man Called Lemkin

From Raphael Lemkin's Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation - Analysis of Government - Proposals for Redress

(Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1944), p. 79 - 95.

Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, published in November 1944, was the first place where the word "genocide" appeared in print.

Raphael Lemkin coined the new word "genocide" in 1943 (see the book's preface, dated November 15, 1943) both as a continuation of his 1933 Madrid Proposal and as part of his analysis of German occupation policies in Europe. In this 670 page book, Axis Rule, Lemkin introduced and directly addressed the question of genocide in 16 pages of Chapter IX entitled "Genocide" (below).

Lemkin uses the word genocide broadly, not only to describe policies of outright extermination against Jews and Gypsies, but for less immediate Nazi goals as well. In Lemkin's analysis Nazi Germany had undertaken a policy for the demographic restructuring of the European continent. Therefore he also used the word genocide to describe a "coordinated plan of different actions" intended to promote such goals as an increase in the birthrate of the "Aryan" population, the physical destruction of the Slavic population over a period of years, and policies to bring about the destruction of the "culture, language, national feelings, religion" and separate economic existence (but not physical existence) of non-German "Aryan" nations thought to be "linked by blood" to Germany.

In recent years the word "genocide" has most often been used to refer to the destruction of groups within a single country ("domestic genocide"). In Axis Rule, however, the word applies to occupation polices conducted across an entire continent. Policies within Germany are addressed only to the extent that these policies impacted Austria, and those parts of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, the Memel Territory and Poland formally incorporated into Germany.

Within Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, Part I: Analysis of "German Techniques of Occupation," 92 pages in length, includes nine chapters of general analysis. In these chapters, Lemkin addresses 1) Administration, 2) Police, 3) Law, 4) Courts, 5) Property, 6) Finance, 7) Labor, 8) Treatment of Jews, and 9) Genocide.

Part II: The Occupied Countries, 167 pages in length, addresses specific aspects of of occupation administration by the Axis powers. In addition to German occupation policies, Part II addresses polices of the other Axis countries: Italy, Bulgaria, Hungary and Rumania as well as the wartime puppet states of Croatia and Slovakia. The 17 occupied countries and territories included in the baook are Albania, Austria, the Baltic States (Lithuania, Latvia & Estonia), Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Danzig, Denmark, the English Channel Islands, France, Greece, Luxembourg, Memel Territory, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, the USSR and Yugoslavia.

The largest section of Axis Rule is Part III: Laws of Occupation is 370 pages in length. Here Lemkin provides English translations of 334 statues, decrees and laws from the 17 occupied countries and territories. Most of the documents are from the years 1940 and 1941, though the collection spans a five and half year period March 13, 1938 to November, 13, 1942. The range of the dates underscores the fact that Axis Rule was a work of analysis of the enemy's public documents written during wartime (and not those captured at the end of the war). These documents were available to Lemkin and others from sources in the neutral countries in Europe.

In the decades since the Second World War, Chapter IX has become the most widely quoted and cited section of Axis Rule. Between 1944 and 1946, however, the entire book was of tremendous value as a reference guide to to war crimes investigators, governments returning from exile and Civil Affairs sections of Allied armies trying to establish order in postwar Europe.

I. GENOCIDE - A NEW TERM AND NEW CONCEPTION FOR DESTRUCTION OF NATIONS

New conceptions require new terms. By "genocide" we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group. This new word, coined by the author to denote an old practice in its modern development, is made from the ancient Greek word genos (race, tribe) and the Latin cide (killing), thus corresponding in its formation to such words as tyrannicide, homocide, infanticide, etc.(1) Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group.

The following illustration will suffice. The confiscation of property of nationals of an occupied area on the ground that they have left the country may be considered simply as a deprivation of their individual property rights. However, if the confiscations are ordered against individuals solely because they are Poles, Jews, or Czechs, then the same confiscations tend in effect to weaken the national entities of which those persons are members.

Genocide has two phases: one, destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the other, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor. This imposition, in turn, may be made upon the oppressed population which is allowed to remain or upon the territory alone, after removal of the population and the colonization by the oppressor's own nationals.

Denationalization was the word used in the past to describe the destruction of a national pattern. (1a) The author believes, however, that this [p. 80] word is inadequate because: 1.) it does not connote the destruction of the biological structure; 2.) in connoting the destruction of one national pattern it does not connote the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor; and 3.) denationalization is used by some authors to mean only deprivation of citizenship.

Many authors, instead of using a generic term, use currently terms connoting only some functional aspect of the main generic notion of genocide. Thus, the terms "Germanization," "Magyarization," "Italianization," for example, are used to connote the imposition by one stronger nation (Germany, Hungary, Italy) of its national pattern upon a national group controlled by it. The author believes that these terms, are also inadequate because they do not convey the common elements of one generic notion and because they do not convey the common elements of one generic notion and they treat mainly the cultural, economic, and social aspects of genocide, leaving out the biological aspect, such as causing the physical decline and even destruction of the population involved. If one uses the term "Germanization" of the Poles, for example, in this connotation, it means that the Poles, as human beings, are preserved and that only the national pattern of the Germans is imposed upon them. Such a term is much too restricted to apply to a process in which the population is attacked, in a physical sense, and is removed and supplanted by populations of the oppressor nations.

Genocide is the antithesis of the Rousseau-Portalis Doctrine, which may be regarded as implicit in the Hague Regulations. This doctrine holds that war is directed against sovereigns and armies, not against subjects and civilians. In its modern application in civilized society, the doctrine means that war is conducted against states and armed forces and not against populations. It required a long period of evolution in civilized society to mark the way from wars of extermination, (3) which occurred in ancient times and in the Middle Ages, to the conception of wars as being essentially limited to activities against armies and states.

Totally Unofficial: RAPHAEL LEMKIN AND THE GENOCIDE CONVENTION

Series Editors Adam Strom & the Facing History and Ourselves Staff Primary Writer Dan Eshet With an

Introduction by Omer Bartov, John P. Birkelund Distinguished Professor, Brown University

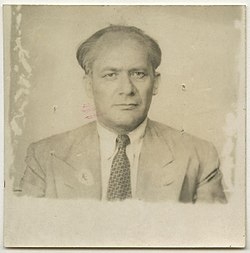

Raphael Lemkin

(June 24, 1900 – August 28, 1959) born in Lviv was a lawyer of Polish-Jewish descent who is best known for coining the word genocide and initiating the Genocide Convention. Lemkin coined the word genocide in 1943 or 1944 from genos (Greek for family, tribe, or race) and -cide (Latin for killing).

Video:

- Genocide Convention - Interview with Mr. Raphael Lemkin

- Conventional Revolution: Raphael Lemkin and the Crime Without a Name