The Red Army liberated northern Norway in the autumn of 1944 and approx. 50% of these were Ukrainians. More than 100,000 women and men, Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians were prisoners of war and slave laborers in Norway in the period 1942–1945. They built roads and railways. They set up the Nazi defenses along the 100,000-kilometer-long Norwegian coast. They worked in agriculture all over the country and in the fish processing industry in Hammerfest and Bodø. They provided "Fresch Fisch aus Norwegen", as it said on the railway wagons with fish sent to Germany.

The Red Army liberated northern Norway in the autumn of 1944 and approx. 50% of these were Ukrainians. More than 100,000 women and men, Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians were prisoners of war and slave laborers in Norway in the period 1942–1945. They built roads and railways. They set up the Nazi defenses along the 100,000-kilometer-long Norwegian coast. They worked in agriculture all over the country and in the fish processing industry in Hammerfest and Bodø. They provided "Fresch Fisch aus Norwegen", as it said on the railway wagons with fish sent to Germany.

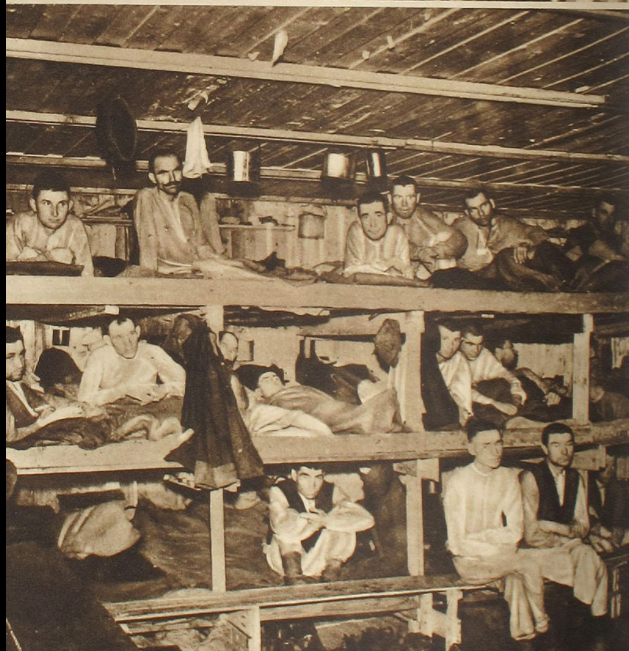

Ukrainian prisoners of war lived in miserable conditions in 500 prison camps scattered throughout Norway. They were starved and abused. They were slaves, an inferior race, who had no right to life.

About 9,000 Ukrainian prisoners of war in Norway did not celebrate the victory in 1945. They died of ill-treatment and starvation and lie in unmarked graves in Norway, many gathered at Tjøtta in Nordland.

(Photo above: http://nordlandsmuseet.no/blodveimuseet/)

Silence and oblivion have been the strategy of the Cold War against the Ukrainian prisoners of war and the fate of forced laborers in Norway during the Second World War. These were both women and men. Many of the fates of the prisoners of war under the yoke of Nazism are still in the dark. A black hole has recently hidden the Ukrainians' existence and efforts in Norway during World War II, and also what happened to them when they returned to the Soviet Union. But new research in both Norway and Ukraine has given us more insight into the fate of Ukrainian prisoners.

women and men. Many of the fates of the prisoners of war under the yoke of Nazism are still in the dark. A black hole has recently hidden the Ukrainians' existence and efforts in Norway during World War II, and also what happened to them when they returned to the Soviet Union. But new research in both Norway and Ukraine has given us more insight into the fate of Ukrainian prisoners.

On June 22, 1941, the German army attacked Ukraine, theb a part the Soviet Union. With the attack came a relentless war. Nearly 3 million Ukrainian soldiers and many civilians were captured in the period after the attack and until February 1945. Over 1.5 million of these prisoners of war died in German captivity. About 50% of the red Army were Ukrainian.

Ukrainian prisoners of war in Norway

During 1941-45, about 50,000 Ukrainian prisoners of war were sent to Norway.

Most of these prisoners were soldiers of the Red Army while about 3.500 were civilian Ukrainian citizens. Of these, close to 700 were women and 200 children.

Humiliation, inhuman toil, hunger and death marked the life of the Ukrainian prisoners of war in Norway. Nevertheless, prison life also had bright spots. Unity among the prisoners and contact with Norwegians outside the barbed wire gave strength.

Forced laborers

Josef Terboven was National Commissioner, head of the highest civilian authority in Norway, only under Adolf Hitler. Reichskommissariat (RK) was responsible for the construction of fortifications, roads, railways and airports for them German military forces in Norway. The Wehrmacht spent money on their own needs and handed it over financial problems of the RK and Norwegian institutions. RK collaborated with German and Norwegian companies on the construction projects. But the responsibility for Hitler RK was not responsible for the largest building plans - it was Organization Todt who was given responsibility for them. This was a semi-military construction organization which i.a. had been responsible for the construction of the Autobahn in Germany. Adolf Hitler, commander-in-chief of the military forces, had personal interests in the construction plans for the Nordlandsbanen being implemented in Norway. These projects was important to the German Empire due to military and supply considerations. Organization Todt was given responsibility for the construction of the Nordlandsbanen, development of Riksveg 50, the defenses along the coast and the construction of a submarine bunker in Trondheim. They put out tenders and companies from all over Europe were engaged in Norway. Another major construction project was the plans Hermann Göring had about six times the aluminum production in Norway by 1944. This was to be used for the armaments industry, specifically for the air force.

The vast majority of the Ukrainian civilian forced laborers who came to Norway can confirm that they was forcibly sent from his home country.

Ukrainian women and men who were in Bodø are said to have been threatened with being deprived of the ration card if they did not report for work in Germany. This was on in the spring of 1942.64 The 150 women in Hammerfest were between 14 and 40 years old, some of them young were picked up directly at the school without being allowed to pack anything. All were driven in freight cars to Szczecin (current Szczecin in Poland). There they were sent in cargo ships directly to northern Norway.

A woman in Hammerfest says that she traveled for three weeks in a row before they arrived. Also those who arrived Nordag in 1943 can tell that they were taken by force.

This story is from a village by Poltava, Ukraine: “Sunday, March 14, 1943, was a date we will never forget. The Germans stated that everyone had to come to the center of the village. There were all the boys and girls who were born in the second half of 1923 and all who were born in 1924, 1925 and 1926 taken and put on trucks; that is, all young people between the ages of 17 and 20. My two younger brothers aged 16 and 14 did not stay taken. ”66 In 1944, there was a recruitment campaign among Belarusian youths and children down to 10 years. Some of these also came to Norway, e.g. three siblings from 11-15 years sent to Mo i Rana,working for Organization Todt.

There were also frozen fillet plants in Melbu and Hammerfest, so the Bodø plant was unable to utilize its full capacity more than the three months Lofoten fishing took place. The facility in Hammerfest was built by a Hamburg company, Vereinigte Tiefkühlgesellschaften Lohmann und Co (Vertilo). It was already up and running in the summer of 1941, and this plant could produce 50 tonnes of fillet around the clock. They used another technology that worked just as well as Frostfilet's freezing technology.

This facility was moved to Svolvær in the autumn of 1944, when the large evacuation of East Finnmark started. The fourth and last frozen fillet plant was built and operated by Norwegians. It was A / S Gunnar Fredriksen's Filet Factory, at Melbu in Vesterålen. In March 1943, the plant was completed, and it could produce 30 tons of fillet per day. Of the four frozen fillet factories in Norway, it was the one in Melbu who answered best. They had a capacity utilization of 36 percent, the plant in Bodø had only 26 percent utilization. The plant in Melbu delivered to the civilian market in Norway, theothers delivered only to Germany and specifically to the Wehrmacht, as field provisions for soldiers on the front. In January 1942, the Government Information Office in London claimed that the factories in London Trondheim and Bodø produced enough to give German soldiers 25 million fish dinners per month.

Slaves on Norwegian soil

Norway's resources were one of the reasons why the foreign forced laborers were sent to Norway. De ca. 4000 ukrainian forced laborers were sent here primarily to build and work on aluminum factories frozen fillet factories. They came here in 1942–1943, only when it became difficult to obtain Norwegian labor.

Norway's resources were one of the reasons why the foreign forced laborers were sent to Norway. De ca. 4000 ukrainian forced laborers were sent here primarily to build and work on aluminum factories frozen fillet factories. They came here in 1942–1943, only when it became difficult to obtain Norwegian labor.

The Ukrainian prisoners of war were used as slave labor by the German occupation forces in Norway. Soldiers captured during fighting in the Balkans and the Ukrainian were put to work on the Germans' extensive construction projects. By order of Hitler, the semi-military organization Organization Todt carried out a number of such projects in Norway and Denmark.

In this country, Ukrainian prisoners of war were used to build railways, roads, airports and fortifications. The commander-in-chief of the German occupying forces in Norway, Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, demanded 77,000 Ukrainian prisoners of war in order to carry out Hitler's plans for a railway to Kirkenes. These plans were not realized, but the Nordlandsbanen railway project was partly completed with the help of the prisoners of war labor.

The first transports of Ukrainian prisoners of war arrived in Norway in August 1941. Many of the soldiers captured in Ukraine in June this year were first sent to Poland or Germany. Then they were stowed in cargo ships and sent to Norway.

From 1942, Ukrainian civilian forced laborers received ordinances that put them in line with Ukrainian prisoners of war. For example, there was a barbed wire fence around the barracks camp, the catering was as poor as the prisoners of war, and it was allowed to beat the workers.

The camps

Exhausted after several days at sea with little supplies and miserable sanitary conditions on board, the prisoners arrived at Norwegian ports. They were sent on by ship or train to an uncertain fate in German prisoner of war camps. The prisoners of war were placed in a camp system with almost 500 prisoner camps throughout Norway, and two thirds of the prisoners were placed in northern Norway.

All military, Ukrainian prisoners of war sent to Norway were first placed in concentration camps, Stalag, or labor battalions under the Wehrmacht. The concentration camps were a major institution for the prisoner of war system in Norway. In reality, they were controlled by the German army, which competed with the Air Force, Navy and Organization Todt for the distribution of prisoners of war for the construction projects.

Little food and bad clothes

Illness was perhaps the greatest danger to prisoners of war in Norway. Diseases such as diphtheria, tuberculosis, diphtheria and pneumonia spread rapidly. Many also died of abuse and starvation. Many camps in northern Norway were in practice pure death camps due to lack of food. In most cases it was approx. a liter of soup for breakfast, lunch was usually leftovers from previous evening meals, bread and coffee, or soup for the evening. On rare occasions, prisoners of war received some meat, potatoes, cheese, or fish.

In addition to the miserable meals, the Germans showed little willingness to equip the prisoners of war with adequate and usable clothing. The miserable conditions became a kind of additional punishment to the captivity. Adequate clothing meant the distinction between life and death for Ukrainian prisoners of war.

On Engeløya in Steigen, 600 Ukrainian prisoners of war worked in the quarry, among other places. About half of these died during their stay. The Germans often beat the prisoners, who became powerless and disabled. Hard work, poor nutrition and inhuman living conditions destroyed the prisoners' health. The discipline in the camp was very strict, and for various transgressions the prisoners were punished with ten to twenty-five or fifty lashes. For theft or attempted escape, the prisoners received fifty lashes.

The German occupation forces regarded escaped Ukrainian prisoners of war as a threat from the very beginning of the war. The reason was the fear of espionage, sabotage and the organization of partisan groups.

The guards often ordered Ukrainian prisoners of war to walk in front of them on their way to work, then shoot the prisoners from behind. They later reported that the prisoners had been shot because they were trying to escape.

The dangerous escape

Ukrainian prisoners of war who tried to flee to Sweden had little chance of success. They usually could not speak Norwegian and were poorly equipped with clothes and footwear. The escaped prisoners were malnourished and had no food. Many were taken along the way, while others died of starvation and cold.

Prisoners on the run were often reported by people in the area around the camps or workplaces. In Norwegian newspapers there were warnings of the most severe punishment to help Soviet prisoners of war escape. The Germans paid well for information about prisoners who had escaped.

Major Leiv Kreyberg from the relief work for released prisoners in Nordland in the spring of 1945 was among the first to see what conditions the prisoners of war had been exposed to. He said that throughout the war, the people in these districts had seen prisoner transports come and go, seen the ragged, hungry and miserable prisoners of war, and noted the mass deaths, partly from disease, partly from murders.

The population had sympathy and care for the abused prisoners. There are many examples of how people in the local community gave food and clothes to hungry prisoners, encouraged them with a smile and in various ways showed that they were their friends. Many helped the prisoners with great danger to their own lives.

The helpers

Eli Holtsmark was twelve years old during the war. The sight of prisoners in the camp at the hospital in Bergen made a strong impression on her:

"We crawled forward until we came to the fence. There were prisoners, gray uniforms, thin and emaciated, but very cheerful. Food was sneaked under the solid prison net. The German guards saw it well, but let it pass. We saw the prisoners eating the packed lunches with obvious joy. The prisoners looked old, with ugly, gray and wrinkled skin. Strong, worn hands. But the eyes were young, so friendly and happy on us. Once I listed food under the fence, a large hand came out and there was a handshake. The German guards let it happen tacitly. Turned halfway away with friendly posture. It developed a habit of bringing food. "

In Ålesund, master painter Johan Hjelmeland was a good helper for the Ukrainian prisoners of war. He tells of the sight of the first group of 100 Ukrainian prisoners of war who came to the city at Christmas 1942:

"It was bitterly cold, and the prisoners had only a few rags on their bodies. On their legs they had straw. Some of them had become ill, some were eased ashore like planks. When they had to line up for muster, many of them were so exhausted that they plunged. Those who could not get up again were thrown on a truck and driven away. It was all outrageous and cruel, and I promised myself that help would be needed here, even if I was going to beg for the rest of my life. "

Female forced laborers

Very young Ukrainian women were also sent to forced labor for the Germans in Norway. In mid-April 1944, 95 female Ukrainian forced laborers came to Oslo from Aarhus in Denmark.

There were 300 women working at the frozen fillet factories in northern Norway, approx. 1,000 for Luftwaffe, 40 during Nordag and a number of women in Organization Todt. The Women in Organization Todt was divided into smaller groups, i.a. to Narvik, Engeløy, Mo i Rana, Trondheim and Oslo. The women were mostly put to kitchen work and cleaning the barracks.

In 1944, a Ukrainian woman asked for Norwegian authorities took care of the newborn child when the German father of the child was dead. It did not happen completed. Only in a third case in Oslo was the child taken from the mother, it is uncertain if it was voluntary or not.

The liberation

At the time of the liberation in 1945, there were around 42 000 Ukrainian prisoners of war on Norwegian soil. Many prisoners of war needed medical treatment.

In June 1945, the Swedish Red Cross took over the German Ortslasarett at Klungset in Fauske. In the course of a month, about 200 Ukrainian patients were treated by Swedish and Norwegian doctors and nurses. There were many cases of severe tuberculosis and hunger edema. The Swedish Red Cross also took responsibility for supplying all camps in Nordland county with diet food as far as possible.

Irina Skretting worked as an interpreter at several prison camps after the liberation in southern Norway and was present when the Norwegians took over Jørstadmoen:

"I never saw worse conditions than at Jørstadmoen. What met us in this camp was indescribable. Especially the barracks with tuberculous prisoners. They were almost isolated from the others. The Germans were also terrified of being infected. The prisoners lay on briskers along the walls. It was so cramped that it was almost impossible to get in and out of the brisket. The sanitary conditions cannot be described either. It was inconceivable that these barracks could have been human habitats. "

Return home

On June 13, 1945, the repatriation of Ukrainian citizens began. All available ships and all transport options through Sweden were used for this purpose. During June and July 1945, about 42,000 freed Ukrainian citizens were sent back to the Soviet Union from Norway. About half of those repatriated this year were of major Ukrainian nationality. But also russians, Belarusians, Georgians, Tatars and other minorities were among those sent home.

At the end of July 1945, the journey home also began for the three sisters from Belarus. With the ship S / S Stella Polaris they sailed from Mo i Rana to Murmansk. The ship was used as an ambulance by released Ukrainian prisoners of war, and some of the prisoners on board were in very poor condition. Some died during the trip.

In Murmansk, the three sisters were controlled by Soviet authorities and then sent home and reunited with their parents.

Forced repatriation

When most of the released Ukrainian prisoners of war were sent home, the question of forced repatriation arose. Soviet authorities and the Allies had different interpretations of who were Ukrainian citizens.

From the Norwegian side, the desire for a good relationship with the Soviet authorities was decisive for the decisions that were made. In the end, there were 1566 people who had not established citizenship and the responsibility for these was left to the allied authorities.

Returned Ukrainian prisoners of war and their fate have long been the subject of speculation. Western writers have in many cases given a one-sided account of the Soviet authorities' reception of prisoners of war, focusing on executions and new captives in concentration camps. The reports of former prisoners of war show that they were usually subjected to a thorough examination after returning home. Recent research indicates that more than half were sent directly home.

The biggest loss on Norwegian soil

About 13,700 Ukrainian prisoners of war died during their stay in Norway, thus this was one of the single group that had the largest loss on Norwegian soil.

However, the exact death toll is still uncertain. This is partly due to the fact that source material was destroyed during the German capitulation. And partly due to the Nazis' lack of respect for human life, when prisoners of war were thrown into mass graves or barely buried.

Today, about 3.500 of the Ukrainian victims are identified by name. Only almost 75 years after the end of the war, it has been possible to identify the names of several of the victims on the basis of German prisoner cards. Under the auspices of the research project Painful Heritage, the information about the identified victims has been made available in a database www.krigsgraver.no where you can search for answers to the fate of the individual prisoner.

At Falstad camp in Nord-Trøndelag, there were about 200 Ukrainian prisoners of war during the war years. The identification of Soviet victims has been very difficult at the war cemetery in Falstadskogen outside the camp. In the summer of 1945, proven burial sites were opened, but most of the names of the approximately 100 Ukrainian victims are still unidentified.

The Cold War contributed to the long history of Ukrainian prisoners of war being pushed out of Norwegian war history.

The events surrounding the so-called Operation Asphalt in 1951 were closely linked to the Cold War policy. This year, the remains of dead Soviet prisoners of war were moved from burial sites in northern Norway to the war burial site Tjøtta on the Helgeland coast. The seven-meter-long monument over the large mass grave at Tjøtta war cemetery reads: "In grateful memory of Soviet soldiers who lost their lives in northern Norway during the war of 1941-1945 and who are buried here."

The monument appears as a symbol of the grave of the unknown soldier, but the war cemetery has several memorials. On a small bauta, 826 of the 7551 Soviet buried victims on Tjøtta are listed with their own nameplates with Norwegian and Cyrillic inscriptions. In 1977, a monument was also unveiled in the war cemetery over the approximately 2,500 dead from the ship "Rigel" which was shot down by Allied aircraft in the autumn of 1944. No monument for the Ukrainian soldiers.

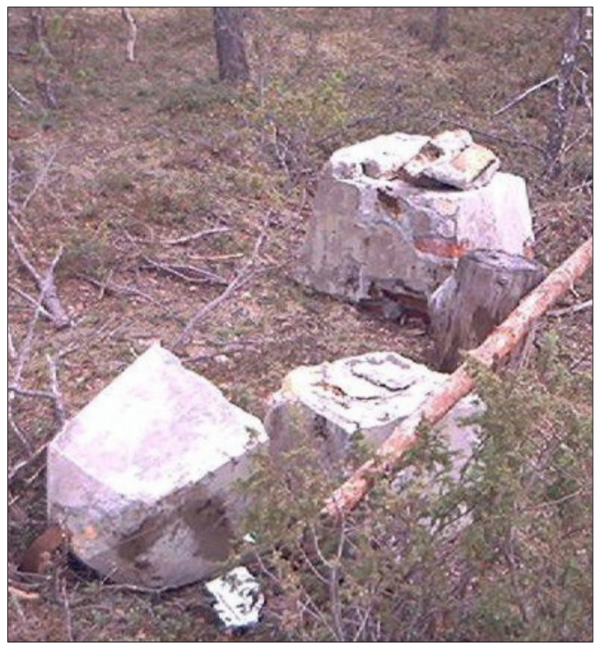

Many monuments were destroyed during the relocation of the war graves. A construction worker experienced in the autumn of 1950 that a grave monument by Bjørnelva was blown to pieces. When asked why this was done, he was told that "it is so scary for tourists to see these Russian grave monuments standing around like this".

Identification of victims

For six years, the nameplates from the mass grave were removed by the Norwegian authorities. This anonymization of named victims was a step backwards for the preservation of the memorial site.

The nameplates are an important part of the memorial site Tjøtta. They convey a forgotten story on Norwegian soil. They also give a unique presence to the story in the form of something as simple as a name, an identity. The nameplates are very important for descendants and relatives of the victims who are looking for information about those who ended their lives in German captivity in Norway.

In 2009, the Norwegian authorities put the nameplates back in place and the names of several identified victims will be made visible at the memorial site. Under the auspices of the project "War graves seeking names", new nameplates with 4800 identified names of Soviet victims were unveiled at Tjøtta war cemetery in the autumn of 2016.

No Ukrainian memorial in Norway

The remains of one of the original supports at Bjørnelva prison camp at “The Sugar peak” on Saltfjellet. A large cemetery where Ukrainian prisoners were buried. Road workers who lived in a barracks here used to take care of it the cemetery (circa 1951). They were horrified to witness that one man got in car and blew up the support. They asked man WHY? After which it was answered: “They are so ugly to look at for the tourists! ”

These are the destroyed remains of the original "Russian" the memorial support at the camp at Hjartåsen in Dunderlandsdalen. This was perhaps the largest of the Ukrainian prison camps in Dunderlandsdalen.

|

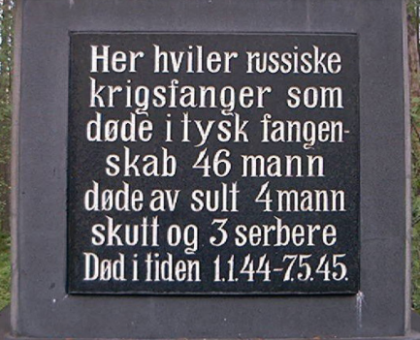

|

|

| This is a very typical treatment of the Ukrainian prisonors of war in Norway. This is a restored original support from the prison camp at Røkland (Pothus). The camp was initially for Yugoslavs, but they were moved to "Lager Polarzirkel" and approx. Many hundred Ukrainians come here. Here at the cemetery, many Ukrainians were aslo buried. This is an excerpt from one inscription page on the support at Røkland (picture to the left). Here is all prioners calles "russians". It is written that 4 "Russians" are shot and 46 died of starvation. Also 3 Serbian prisoners of war were buried here. | ||

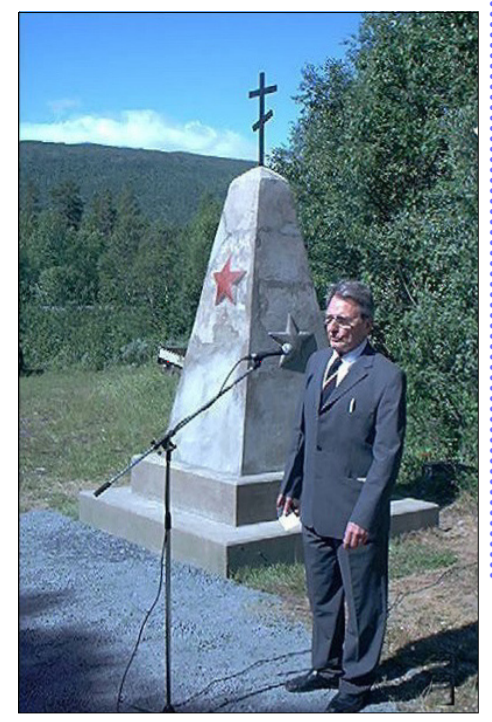

The newly built memorial support at Hjartåsleiren. The unveiling took place in July 2003. The russian Alexei Perminov gives a speech.

Where is the Ukrainian flag and where is the Ukrainian speech ? About 50% of the red Army was Ukrainian.

Source:

The State Archives in Tromsø

Troms Police Department. 2374. Name list of the prison camp Tromsdalen.

Michael Stokke: Soviet and French civilian forced laborers in Norway 1942-1945

Marianne Neerland Soleim: Soviet prisoners of war in Norway 1941-1945: number, organization and repatriation, Oslo 2009

Comments powered by CComment