Raphael Lemkin, the distinguished lawyer who coined the term “genocide” and is considered the father of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide adopted by the United Nations on December 9, 1948 (the U.N. Convention on Genocide), regarded the Holodomor as a part of the Soviet genocide against the Ukrainian people. (Rafael Lemkin, “Soviet Genocide in Ukraine,” New York, 1953,

Raphael Lemkin, the distinguished lawyer who coined the term “genocide” and is considered the father of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide adopted by the United Nations on December 9, 1948 (the U.N. Convention on Genocide), regarded the Holodomor as a part of the Soviet genocide against the Ukrainian people. (Rafael Lemkin, “Soviet Genocide in Ukraine,” New York, 1953,

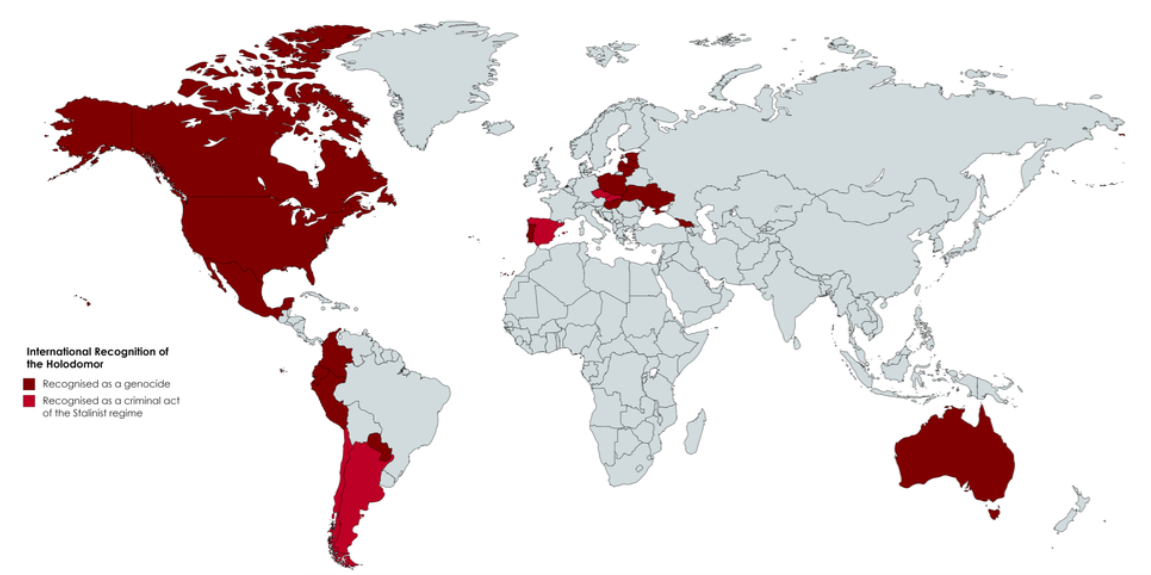

Yet recognition of the Holodomor as genocide on the international level still is not universal.

The last saturday in November Ukrainians throughout the world will light the candles as a symbol of remembrance of the most horrible tragedy in the history of Ukraine, which claimed millions of innocent lives. Those were the victims of the Holodomor of 1932–1933, the man-made famine planned and implemented by the communist Stalin’s regime.

Holodomor was recognized by the Ukrainian Parliament as the genocide against the Ukrainian people. For decades this appalling act of inhumanity and an immense national tragedy have been kept a secret by the Soviet Union, vehemently denied by the communist regime and largely unknown to the world.

Millions of people, mostly the peasants – the backbone of Ukrainian identity, culture and traditions, within two years were literally starved to death by the policies of Stalin’s regime, who sought submission to the Soviet rule and resolution of the “Ukrainian issue”. The findings of the work carried out by the Institute of demography and social research show that of all the victims 93% were rural residents.

Based on study of available statistics, at the height of Holodomor, Ukrainians died at a rate of 25,000 per day.

In the same two years, the Soviet Union sold 1.7 million tons of grain on western markets.

We once quoted in the Permanent Council a renowned expert in international criminal law Raphael Lemkin, who researched and developed a concept of genocide, and whose many ideas were incorporated into the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide in 1948, who described the Holodomor as “not simply a case of mass murder but as a case of genocide, of destruction, not of individuals only, but of a culture and a nation”.

Based on the facts of this horrible crime that could only be brought to light only 2 after Ukraine regained independence, now the overwhelming majority of Ukraine’s population, 79% according to one of the latest surveys, hold the informed view that Holodomor was genocide.

We are concerned that there are ongoing attempts by one country to dismiss facts and deny this horrendous crime of genocide committed by the communist Stalin’s regime against the Ukrainian people.

Despite Russia’s denial of the Holodomor, over the years Ukraine has always felt the support and solidarity of the international community in establishing the truth about one of the greatest crimes against humanity in the world’s history and in paying proper tribute to its victims.

National parliaments and regional assemblies in many countries of the world have also recognized Holodomor as genocide. Millions of innocent victims of Holodomor who were killed by barbaric policy of the Soviet totalitarian regime, we stress the importance of remembrance and maintaining a firm stance in condemning totalitarianism, regardless of the colours it used, and strongly upholding the values of democracy, human rights and freedoms.

For those countries that have not yet recognized Holodomor as a genocide, we encourage you to send us a message and together we will demand your country's recognition. We are now working for Norway to recognize Holodomor as a genocide.

- Recognition of Holodomor as genocide: To the Norwegian Parliament and the Norwegian Government

- Please sign this signature campaign.

It is a shame for Norway that they have not yet recognized Holodomor as a genocide. Norway who otherwise wants to be at the forefront when it comes to human rights.

We encourage all nations to adopt recognition.

- States that recognized Holodomor as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people (eksternal link)

The UN Convention on Genocide of 9 December 1948

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948 and came into force on 12 January 1951. Soviet Ukraine became a signatory of the Convention on 16 June 1949 and ratified it on 15 November 1954. Independent Ukraine continues to respect the international Convention and has inscribed "Article 442. Genocide" into its own Code of Criminal Law.

The term "genocide" was coined in 1943 by Raphael Lemkin (1900-1959) "from the ancient Greek word genos (race, tribe) and the Latin cide (killing), thus corresponding in its formation to such words as tyrannycide, homicide, infanticide, etc." A Polish Jew, born in what today is Lithuania, Lemkin studied law at the University of Lviv, where he became interested in crimes against groups and, in particular, the Armenian massacres during the First World War. In October 1933, as lecturer on comparative law at the Institute of Criminology of the Free University of Poland and Deputy Prosecutor of the District Court of Warsaw, he was invited to give a special report at the 5th Conference for the Unification of Penal Law in Madrid. In his report, Lemkin proposed the creation of a multilateral convention making the extermination of human groups, which he called "acts of barbarity," an international crime.

Ten years later, Lemkin wrote a seminal book on the notion of genocide. A short excerpt will show that the author's approach was much broader than the one later adopted by the UN:

"Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group."

Lemkin's book became a guiding light for the framers of the UN Convention on Genocide.

The Convention voted by the UN General Assembly contains 19 articles, dealing mainly with the problems of the prevention and punishment of genocidal activity. Most relevant to our discussion is the preamble and the first two articles. The preamble acknowledges that "at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity," while the first article declares that genocide is a crime under international law "whether committed in time of peace or in time of war." The all-important definition of genocide is contained in Article II:

"In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such."

This definition was a compromise after much discussion by the delegates of various countries who sat on the drafting committees. It satisfied few people and continues to be criticized by legal experts, politicians and academics. However, it remains the only legal definition sanctioned by the UN and operative international courts.

A major objection to the definition is the restricted number of recognized genocide target groups. Coming in the wake of the Second World War and informed by Lemkin's work and the evidence of the Nazi concentration camps, the definition would necessarily be tailored to the Jewish Holocaust. Jews could fall into any one of the four categories: national, ethnic, racial and religious. They did not form a political or a social group, but this was not the reason for the exclusion of the two categories, which, after all, were part of Lemkin's concern. The exclusion of social and political groups from the Convention, to which Luchterhandt alluded, was the result of the Soviet delegation's intervention. The implication of the definition's limitation to the four categories of victims is that one cannot argue for the recognition of a Ukrainian genocide if its victims are identified only as peasants. Of the four human groups listed by the Convention, it is quite clear that Ukrainians did not become victims of the famine because of their religious or racial traits. This leaves two categories: "national" and "ethnic(al)."

There has always been a certain ambiguity about the distinction between the two groups labeled as "nation" and "ethnic(al)" by the Convention. William Schabas, internationally recognized legal expert on genocide, believes that all four categories overlap, since originally they were meant to protect minorities. He argues that "national minorities" is the more common expression in Central and Eastern Europe, while "ethnic minorities" prevails in the West. But if both terms designate the same group then there is redundancy, which Schabas fails to note.

A more meaningful interpretation of "national group" was given in a recent case cited by the author. "According to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the term 'national group' refers to 'a collection of people who are perceived to share a legal bond based on common citizenship, coupled with reciprocity of rights and duties'." What we have here is a "civic nation" formed by all the citizens of a given state, regardless of their ethnic, racial or other differentiation, as opposed to "ethnic nation," or members of an ethnic community often divided by state borders. Such a clarification of the terms "national" and "ethnical" in reference to "groups" used would remove any ambiguity or redundancy in the Convention. It would also help the understanding of the Ukrainian famine-genocide.

Relevant to this discussion is a statement made in 1992 by a Commission of Experts, applying the Genocide Convention to Yugoslavia: "a given group can be defined on the basis of its regional existence ... all Bosnians in Sarajevo, irrespective of ethnicity or religion, could constitute a protected group." The "regional" group is thus analogous to the civic national group.

The decisive element in the crime of genocide is the perpetrator's intent to destroy a human group identified by one of the four traits mentioned above. When applying this notion to the Ukrainian case, certain aspects of the question of intent as used by the Convention should be taken into consideration. First, it is not an easy task to document intent, for as Leo Kuper pointedly remarked, "governments hardly declare and document genocidal plans in the manner of the Nazis." However, documents which directly reveal Stalin's intent do exist, and there is also circumstantial evidence which can be used.

Secondly, contrary to frequently erroneous claims, the Convention does not limit the notion of genocide to an intention to destroy the whole group; it is sufficient that the desire to eliminate concern only a part of the group. This implies that there is the possibility of selection on the part of the perpetrator from among the victims within the targeted group, and this aspect must not be neglected when analyzing the Ukrainian genocide.

Thirdly, the Convention (Article II) lists five ways in which the crime is executed:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to the members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

All of these acts, to a greater or lesser extent, can be documented in the Ukrainian experience. Fourthly, the Convention places no obligation on establishing the motive behind the crime, even though the reason behind a criminal's activity can help to establish his intent. Two Canadian scholars with long experience in genocidal studies have classified genocides in four groups according to their motives. It should be clear from examining the list that the Ukrainian genocide fits all four categories:

- To eliminate a real or potential threat;

- To spread terror among real or potential enemies;

- To acquire economic wealth; or

- To implement a belief, a theory or an ideology.

Schabas approaches the problem somewhat differently: "There is no explicit reference to motive in article II of the Genocide Convention, and the casual reader will be excused for failing to guess that the words 'as such' are meant to express the concept."

Yes, to a certain extent. With the help of a criminal ideology, perpetrators of genocide can transform a targeted group into an object of blind hate, which then in itself becomes a motive for the destruction of members of that group. In other words, members of a group "X" are singled out for destruction because they are members of that group. But the underlying motives which brought about the hatred do not disappear - they are only pushed into the background.

Comments powered by CComment